My name is Kinjal Vasavada, and I’m a second year medical student at Tufts University School of Medicine. My passion lies at the intersection of healthcare and human-centered design, where I believe some of the world’s most complex and interesting problems lie. My experiences as a photojournalist, design researcher, and strategy consultant prior to medical school have driven me to approach my medical training as an extensive need finding exercise, grounded in the stories and lived experiences of the patients, providers, and hospital staff around me. I’m always in search of stories and ways to visualize them.

One of the biggest gifts of my medical training has been the longitudinal relationships that I’ve had the opportunity to develop with patients. Through the Tufts Obstetric Patients and Their Students (TOPS) Program, I was buddied with medically and socially complex pregnant patients at local hospitals, to support them in whatever ways they’d like throughout their pregnancy. It was through this program in August 2019 that I first met Adriana, who was then five months into her pregnancy. The nature of our relationship grew from me being her buddy (accompanying her to all her prenatal appointments) to her support (maintaining continuity and checking in about her needs via text messaging). Through ongoing conversation, I heard stories about her experiences inside and outside the hospital – what keeps her up at night, what’s important to her, and what she dreams for herself and her growing family. I began to see my role shifting into one of an advocate, speaking up and asking questions to make sure that Adriana received care that aligned with her needs, aspirations, and values.

Adriana’s story illustrates some of the challenges and joys experienced by growing families in the United States. With her consent, we conducted several in-depth interviews and photography sessions during her hospital stay – structured much like the photojournalism and design research work that I’ve known and loved. What resulted from this work are stories and visuals of Adriana’s lived experiences of pregnancy that she is excited to share with growing families like hers, as they navigate an exciting, yet often harrowing time in their lives. This is for them, as well as for the providers, healthcare systems leaders, policymakers, and entrepreneurs, who build and staff the systems that Adriana has been navigating.

Just Breathe: part 2

Just Breathe: part 3

Content Warning: mental health & substance abuse topics discussed

The day before labor

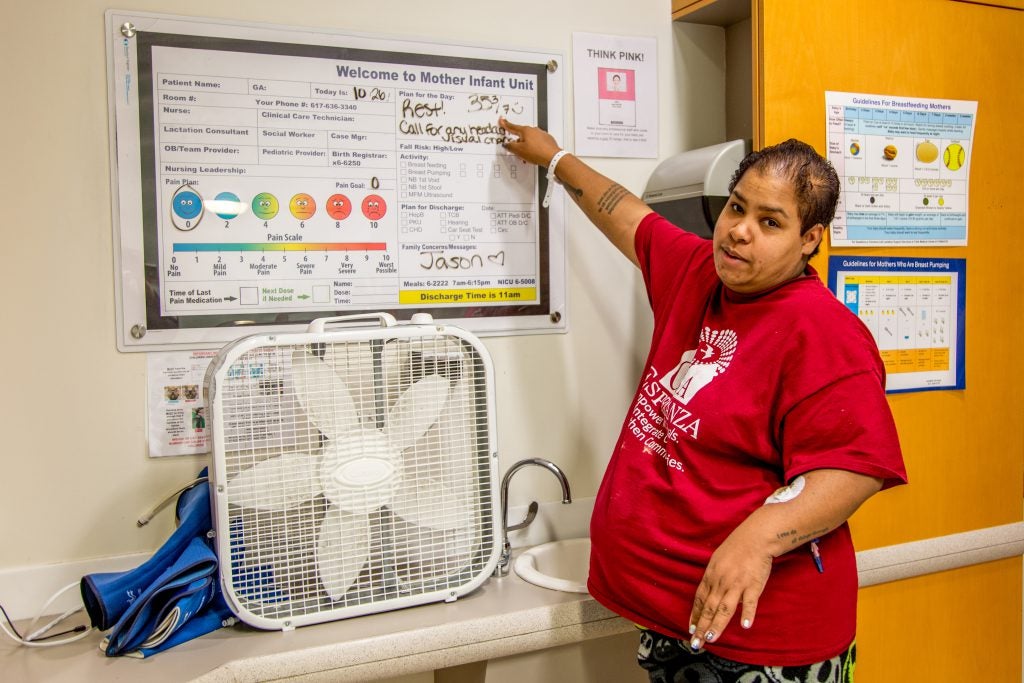

Every day Adriana looks forward to when the nurse updates the number on the board. Today it’s 36 weeks and 6/7 days. Days in the hospital are mundane yet tiring, especially when leaving the room isn’t an option. Adriana passes her time shuffling through the breastfeeding pamphlets and the channels on the ceiling-mounted TV. Or she’ll take naps between the gentle (though sometimes rude) awakenings starting 6:30 am for the routine vitals, blood sugar checks, and non-stress tests. Adriana has many visitors from various hospital floors – doctors, nurses, social workers, nutritionists – each entering with important topics to discuss while their captive audience is recovering from the drowsiness of last night’s Benadryl. “I’m not fully there.”

Adriana Robles is a 28 year old female of Puerto Rican descent expecting her first child. She was admitted to the Mother Infant Unit at 35 weeks into her pregnancy due to pre-eclampsia, a pregnancy complication characterized by high blood pressure that can progress to organ damage and seizures. Because of the pre-eclampsia and how far along in her pregnancy she was, Adriana was told she would be closely monitored until she hit 37 weeks gestation, at which point her delivery would be induced. Yet today, a day away from 37 weeks, she says, “I don’t know who’s part of my team…we don’t know what’s happening tomorrow or Thursday or Friday…there’s no plan.” Every morning around 7 am, “somebody from downstairs with a big paper comes in like ‘Adriana, hi, how are you feeling…any changes?’ And then they’ll tell me the same thing. Thursday’s the day…They’re planning on checking my cervix today so they can see if tomorrow I can start the process…get induced…and deliver the baby. But I have yet to have my cervix checked and that’s the last time I saw the attending doctor. It’s aggravating. My support systems want to know what’s going on…what am I supposed to tell them?”

When it comes to positive birth experiences, only ~42% of mothers in the US report feeling confident during birth. The strongest predictor of that is confidence going into labor, which is heavily impacted by communication between providers and mothers around the decisions, timing, and logistics of care. Research has shown that mothers who have never met their provider before delivery have lower odds of reporting confidence during birth. Moreover, a national survey reported that more than a quarter of Black and Hispanic mothers meet their primary birth attendants for the first time during childbirth, compared with 18% of white mothers.

Modern labor and delivery units “are extraordinarily complex and fraught with uncertainty regarding when patients will arrive, how they will progress, and what their future needs will be.” (Dr. Neel Shah) While the complexity and the flow and shift changes of labor and delivery units can explain difficulties in care coordination, the racial disparity remains to be explained. The anxiety this experience caused Adriana is hard to ignore: “My boyfriend and I are having doubts about me giving birth here.”

Prior healthcare experiences

Since her childhood, Adriana has had a series of health experiences where her concerns were dismissed, and diagnoses were left somewhat unexplained. One of them occurred at age 15, when she was diagnosed with Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal condition characterized by male pattern hair growth, irregular menstrual cycles, and infertility. “They just gave me a pamphlet, ‘here read this,’ and said ‘you’re all set. You have a cyst in your ovaries, that should go away on its own.’ That was all I knew for years.”

After seeking care from many different providers and taking a decade long hiatus from the healthcare system, Adriana finally met E, her primary care provider (PCP). “We have a great bond. She made me feel really comfortable. She’d walk me through the process of what she was going to do. She’ll tell me, ‘I’m gonna go grab these gloves, put ‘em on, and check your back and then have you lay back,’ instead of grabbing stuff and telling me to lay back. I like that consistency of being told what she’s doing as she’s doing it. That way if I have a question as she’s doing something I ask in real time. I like that a lot because it was something I needed growing up that I didn’t get. Getting that from a PCP is great.”

E was also the first provider to assess Adriana’s depression symptoms and severity, get Adriana on medication, and help her quit smoking after nearly a decade.

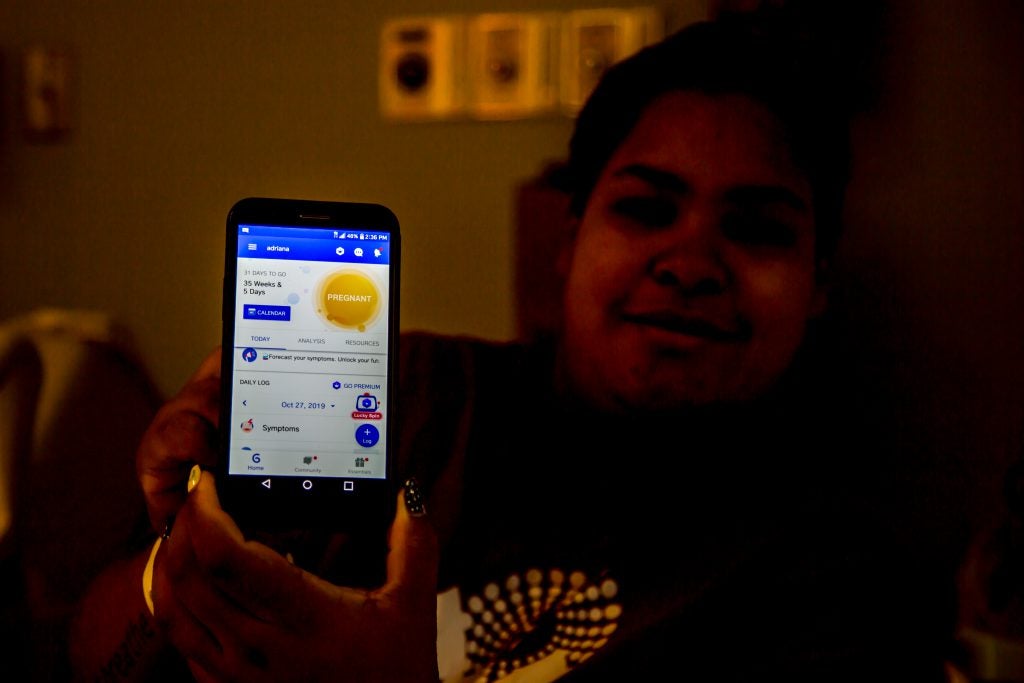

How the pregnancy began – the app

A few months later, Adriana arrived at E’s office with a positive pregnancy test. A part of her truly wanted to believe that her home pregnancy tests were incorrect. Adriana remembers the first time she met her partner Jason: “I went home and told my mom, ‘I think I met my husband today.’” Adriana and Jason had decided that they wanted to have kids together. But not now. Jason was awaiting a trial, and they didn’t think the time was right. Adriana had been using the Glo app to track her period and ovulation dates, yet with period irregularities due to her PCOS and recent appendix removal surgery, her projected ovulation dates proved incorrect. “We just followed whatever the app said – don’t ever do that. It’s not 100% accurate, but I put so much trust in the app.”

Like Adriana, many have echoed frustrations about their period tracking and digital contraception app’s inability to account for changes in their health status (events like surgery and abortion) and the events’ impacts on their menstrual cycles. In the past few years, period tracking and digital contraception apps have come under fire for a multitude of reasons – including being marketed as effective contraceptives (and failing), being designed by men for men, and failing users who don’t fit the archetypal user with regular cycles.

As Adriana processed her feelings of betrayal, confusion, and shock, her phone would buzz with notifications like this one: “Your baby is as big as a spaghetti squash!”

Early anxiety about the pregnancy

Adriana shared the news of her pregnancy with Jason via a text message. “It was just awkward. I didn’t know what to say, he didn’t know what to say.” For Jason, the anxiety kept him from making it to her first prenatal appointment, but photos from the first ultrasound and news of a healthy baby grounded him in a reality that he looked forward to.

For Adriana, the panic didn’t set in until her 3 month ultrasound. She and Jason were sitting in the ultrasound room, drinking tea, and the negative thoughts began to brew. “I’m not sure what I should be seeing. I don’t feel a thing. What if it’s not there anymore.” Then the ultrasound began and what appeared on the screen truly looked like a human baby. “Internally I was freaking out. I didn’t want anyone else to notice, but I didn’t realize I was actually full blown crying.”

For years, Adriana has struggled with depression and anxiety. Nearly one in five mothers worldwide experience perinatal mood and anxiety disorders. This rate is higher in Latina mothers according to a California state level survey, which reported that during pregnancy, nearly 13% screened positive for depression and 22% for anxiety.

“I wasn’t taking the medication I used to before I got pregnant. My brain works in a different way. It was telling me all these negative things while everyone was saying all these positive things like ‘having a baby is great, you’re going to love it, your motherly instinct will kick in.’ My boyfriend keeps telling me ‘you’re going to be a great mom.’ I’m afraid I’m going to be a horrible mother. What if I have this baby and he’s crying at night and I just lose it? That was one of my biggest fears. They’ll call DCF (Department of Children and Families). I will go to jail or they might take the baby away from me.”

“I’m never going to use again”

As a treatment coordinator, substance abuse counselor, and recovery coach, Adriana works with mothers in recovery, and is a mandated reporter of child abuse per section 51A. “Anything can happen to baby while the baby is with the mom, and if we [or the hospital] feel like it was a sign of abuse, we file a 51A.” One experience in particular that stuck with her was of a mother in recovery who ended up losing custody of her 5 month old baby, relapsed, and left the recovery program. “This was one of the hardest things I’ve had to witness – watch a mom relapse because she can’t get her son back. Watch her leave, not know where she’s going, whether she’s going to be safe…”

Every day in her work, Adriana witnesses the psychological, social, and legal consequences faced by mothers who use substances during pregnancy. The fear of these consequences drives many mothers to distrust providers’ screening efforts and to disengage from medical care during their pregnancies.

Adriana herself has struggled with and been in recovery for a substance use disorder. Her history, in addition to her experiences at work, have strengthened her commitment to remaining substance-free. “I don’t want to use again. If I slip and use, I’m putting the baby in danger. They’ll take the baby away from me. My family will hate me, Jason will be pissed off at me.”

“I haven’t touched pills in so long…I should be fine as long as I’m on my medications.”

Growing up

“I think I’ve always had depression and anxiety – just the way I grew up, in a dysfunctional family that was using drugs. My dad was very abusive. He wasn’t a functional addict. But my mom was. She could do coke and clean, cook, bathe us, do our hairs, help us with our homework. We never knew she was using. We knew our dad was.

With all the abuse and yelling, we never knew what we were walking into. Every day was something different. Them arguing, things breaking, my mother trying to hide from him. It was too much. My sister and I were seven or eight years old. I didn’t start cutting until middle school, because it helped. Didn’t start smoking cigarettes until I was 15. The anxiety diagnosis came in then.

I was given benzos for anxiety but ended up abusing it because one wasn’t enough. Six wasn’t enough. I got into the habit of eating it like it was candy, lying to the doctors to get more. They stopped and then my friends were giving it to me because they were taking it.

It was two days of me not taking it, and I was shaking, sweating, emotions all over the place. I was miserable. My mom was drunk, and I told her that she makes me want to commit suicide, and she said, ‘Well do it,’ and I said, ‘Yeah I will.’ She didn’t mean it that way, and I know she was pissed off at me because I was acting strange. I was detoxing at the time and no one knew. I left, walked to the liquor store…got a bottle of Malibu…and starting drinking it. I was standing by the bridge. Stood there drinking. Everyone – my mom, my sister, my cousin’s girlfriend – was calling me. I just wanted the pain to end.”

Since then, Adriana has been on medication for depression and anxiety – until she got news of her pregnancy.

Part 1 Reflections

Stories from Adriana’s early pregnancy surfaced many insights and opportunities around how healthcare systems can better serve their patients, including:

- Healthcare systems are set up to optimize their own workflows and convenience, instead of their patients’ needs, aspirations, and values. How might healthcare systems prioritize patients?

- Healthcare system workflows and variation cannot explain the racial disparity in care and outcomes. How might healthcare systems actively tackle racial disparities in the quality and outcomes of their services?

- Patients have differing expectations around the amount information they’re given about their care and their level of involvement in their own care. How might providers and healthcare systems better appraise each patients’ needs and deliver “precision experiences?”

- As patients access care through different providers, clinics, and healthcare systems, each touchpoint owns a fragment of information. No one except the patient themselves is responsible for knowing their full journey of care experiences. How might we tell a coherent story of a patients’ lifetime of care experiences? How might providers and health systems get on the same page about an individual patient?

- For mothers with current or historical substance use, accessing the medical care they need can be scary. How might healthcare systems and providers help these mothers feel safe about accessing care and being honest about their use, while prioritizing what’s best for them and their kids’ health and safety?

The next installment of this series will explore Adriana’s challenges navigating mental health, the demands of her workplace, and feeling heard in clinical care delivery environments.