This is the third part of Kinjal Vasavada’s three-part photo essay following her medical school buddy, Adriana, through her pregnancy. Catch up on part 1 and part 2.

Content Warning: mental health & substance abuse topics discussed

Food

Adriana pauses to order her lunch: roast beef sandwich on whole wheat bread with a side salad. “I’m figuring out how to navigate this menu,” she says, and the hack, she’s learned, is to avoid not only the stuff with the sugar, but also the carbs.

For Adriana, information around healthy choices in a language she understood was a compelling motivation to make changes. “I didn’t know that whatever I ate was going into the fluid of the placenta – anything I eat, baby can taste it. I learned that at 30 weeks. It popped up on the what to expect app. And I added more fruit and veggies to my diet.”

Navigating food has always been a challenge for Adriana. Food stamps and affordable healthy meal options near her workplace have helped. She knows that she can’t eat the rice her mother makes at home every day. On the day of her baby shower, while all her guests dined a hearty meal with rice and pork, Adriana made herself a salad. But the story of the day before her hospital admission is a poignant illustration of the challenge ahead – Adriana had spent the entire day with her family moving her stuff into her mother’s home in preparation for the baby’s arrival. She hadn’t eaten much the whole day and was really hungry. So on their ride home, they pulled over, and a family member went to grab her a snack. He came back with…chips.

Between chips on the table, a diagnosis of gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes, and a nutritionist referral five weeks from now, Adriana felt frustrated and stuck. Making healthy choices continues to be difficult, because of the systems – family and neighborhood, for example – that Adriana lives and works within.

Aspirations for baby

For Adriana, her pregnancy has been full of changes, big and small, in preparation for her baby boy and the life she and her partner Jason aspire to give him.

“I was picky with food as a kid. My mom had a tendency of force feeding me because I wouldn’t eat. One time, she’d made mac and cheese with some mayonnaise, and was trying to feed it to me and I said no. She forced it in my mouth and forced me to swallow it. Forced me to stay on the table. I was going to sit at that table the entire night until I ate it.

I kept telling myself I don’t want be that kind of mother. I want to give my son options. I can have a conversation with my kid and train him to talk through his emotions. ‘Have your tantrum. Now talk to me. What happened? What caused it?’ Kids don’t have to be yelled at and spanked. I don’t want to lay hands on my son.”

Adriana’s desire reflects a core principle of attachment theory, which postulates that a child’s relationship with their primary caregiver provides a psychological immune system of sorts, that the child can rely on to successfully navigate psychological problems and distress as they grow.

“My boyfriend is onboard with that because of the way we grew up. We don’t want violence in the house. We’ll be stern but don’t want to yell. I want him to have a WHOLE different childhood. I want him to learn what it is to be a man and how to love and respect a woman – or man. I want my relationship with his father to be something he can look up to.”

One in six adults in the US has experienced four or more types of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), including household violence and instability and psychological, physical, or sexual abuse. ACEs have been shown to cause profound and lasting changes in a child’s developing brain and to increase risk of chronic disease, substance use, mental health conditions and other health risk behaviors throughout life. ACEs are more prevalent among female, Black, and Hispanic children, and growing evidence suggests that the health impact of ACEs can be transmitted across generations.

“When my sister and I were seven or eight, my mom showed us a big book with different shapes of pills. I always said I’m never going to smoke – I ended up smoking at the age of 15. Said I’m never going to use drugs – ended up abusing my prescription drugs. We never talked about it when we were in middle school or high school. Once it was said, it was said. No need to be repeated. But I experimented more as I got older. If we’d had that conversation later, it might have turned out differently. I might have had the confidence to say ‘hey Ma, I’m taking this and I’m abusing it.’ Instead of taking it and not saying anything because I’m terrified that she’s going to hit me.

When my son is old enough to understand, I’m going to tell him my mental health diagnosis. His dad will do the same thing. We’re going to talk about addiction because it runs in the family, and he’s predisposed to it already. We will constantly talk to him about mental health, substance use disorder, and talking through your emotions. When he gets older if he wants to smoke or uses drugs, [we’ll ask that he] come to us. Let us know, ‘hey Ma, I tried coke for the first time. Ma, I had a beer.’ So that we can talk about it; how did it feel? So we can prevent addiction.”

According to the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), an average of 8.7 million children aged 17 or younger live in a household where at least one parent has a substance use disorder (SUD). Family history is one of the most potent risk factors for developing an SUD, with an eight-fold increased risk among relatives of a person with SUD. Children who grow up in families with an existing SUD are at significantly higher risk of developing it themselves due to genetic and environmental factors, in addition to being at risk for mental health and behavioral disorders and academic, social, and family function difficulties. Beginning a conversation about substance use as a family has been shown to produce favorable outcomes for the whole family.

Changing Relationships

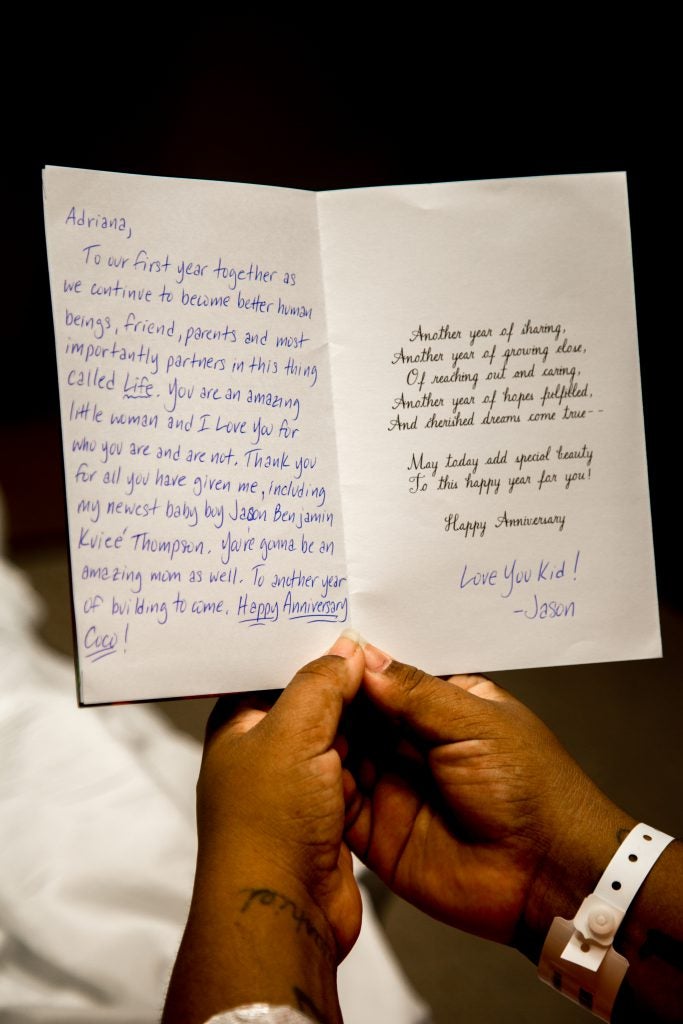

In making her vision for her baby boy a reality, Adriana has driven changes in her relationships with Jason and other family members, who are her primary support.

Adriana looks forward to the short stints of phone time she gets with Jason. “He gives me support on the phone which is what I need. I thought if he were here, everything would be better. He’s been very supportive even though he’s not physically here.” Of the many providers that Adriana has interacted with, very few have actually asked about her partner. One of them was a medical student who stepped out halfway through taking Adriana’s medical history when Adriana got a phone call from Jason. When the student returned, her first question to Adriana was, “How’s dad doing?” Adriana smiled. “He’s here,” she reflects later. “They just don’t realize it I guess.”

Midway through her pregnancy, Adriana reconnected with her father, and over a meal at Chili’s, the two talked about what their relationship would be like once the baby arrived. Adriana also took the opportunity to have a conversation with her mother. “My mom and I came up with an agreement: if she wants to smoke, she goes outside the house. Not the hallway or porch, but outside, where the sun shines. She has to wash her hands, face and change her shirt. I can’t afford for her to smoke and have my son smelling that. He has two parents that don’t smoke, even though I’m a former smoker. I don’t like the smell of it and I don’t want the baby to smell it.” Secondhand smoke exposure has known impacts on infants, including asthma attacks, respiratory and ear infections, and sudden infant death syndrome. Minimizing smoke exposure for her baby was important to Adriana, especially since her mother will be taking care of the baby when she returns to work.

Grandparents, like Adriana’s mother, play an increasingly important role in US households, with nearly 7 million grandparents living with at least one grandchild under the age of 18. Of those grandparents, 39% are responsible for most of their grandchildren’s basic needs. For Adriana, grandmother’s help is key for her return to work.

Baby Shower

A few days before she was admitted to the Mother Infant Unit, Adriana’s family, friends, and friends of the family came together for her baby shower. They gathered in the home that she, her mother, and her sister have lived in since her childhood. The warm brown tiles and low lying ceilings were adorned with colorful streamers and round paper ornaments. Amidst a table full of finger foods lay double layered cake that hoisted up a large letter “J,” the first letter of the baby’s name. In their living room full of bamboo plants and large couches lay a dark glassy painting of a cheetah that was as old as Adriana’s sister, but looked new because of the discipline with which her mother cleaned it all these years.

Family members arrived with giant gift bags – a bassinet, a mickey mouse onesie that the baby would wear when he first arrived home. As people filtered in, the reggaetón on the speakers blended with the sound of kids playing in the stairwell, coronas clinking, and adults bantering.

Adriana’s mother was a busy host: “Do you want some soda? Rice? Beer? Rice, salad, spanakopita, pork – let’s make you a plate!”

In the midst of a conversation, Adriana’s father shared, “I’m so proud of Coco (Adriana).”

Adriana’s journey has been filled with challenges and change, and a small village of family and friends who are mobilizing in support of her and Jason’s dream for their son’s life. Social support is critical in helping pregnant mothers and growing families cope with the stresses of having a baby. Research has shown that pregnant mothers with high quality prenatal support and larger social networks are more likely to have higher birth weight babies and lower rates of postpartum depression.

Conclusion

On November 8th, 2019, after 44 hours of labor and 33 minutes of pushing with her mother and OB/GYN doctor by her side, Adriana gave birth to baby boy Jason Benjamin “Kuieé” Thompson. Both mother and baby were in good health. “The medical team took really good care of me. My boyfriend was so happy our son was born healthy. He was really worried about the preeclampsia. My family is very happy. It was very emotional for me.”

Baby Jason’s birth is only the beginning of Adriana and her partner’s journey as parents, and the many joys and challenges they will experience as they navigate the world with a new addition to their family. With baby Jason as their guiding light, both parents are making changes in their lives. Their success depends on the ability of the systems around them – their families, friends, neighborhoods, and workplaces – to change with them. As individual players and systems respond and reach a new equilibrium, the question remains: will it be everything that Adriana and Jason dreamed?

Adriana’s aspirations for her baby and her family, and the barriers she faces in her effort to make those aspirations a reality, are a compelling mandate to systems in our society to commit to the success of families.

- Pregnancy and the arrival of a baby is time of change and shifting priorities for growing families. How might we support families in making healthy behavior and lifestyle changes during that time?

- Grandparents are increasingly becoming primary caregivers for infants and children. How might we better support grandparents’ evolving roles and responsibilities in US households? How might providers engage grandparents as promoters of family health?

- Family history is a potent risk factor for substance use disorder, and talking about improves outcomes for the whole family. How might providers and healthcare systems promote family conversations around substance use disorder?

- Adverse childhood experiences have profound impacts on all aspects of a person’s life, especially their health. How might healthcare systems and providers support the prevention of ACEs and provide trauma-informed care to patients who have experienced ACEs?

- Social support is protective for mothers and their infants during and after pregnancy. How might we promote social support as a component of healthcare?

- Expecting mothers have aspirations and visions for their growing families. How might healthcare systems and providers best support these aspirations and visions and use them as a guide for care? How might we empower growing families with the dignity and respect that every family deserves?