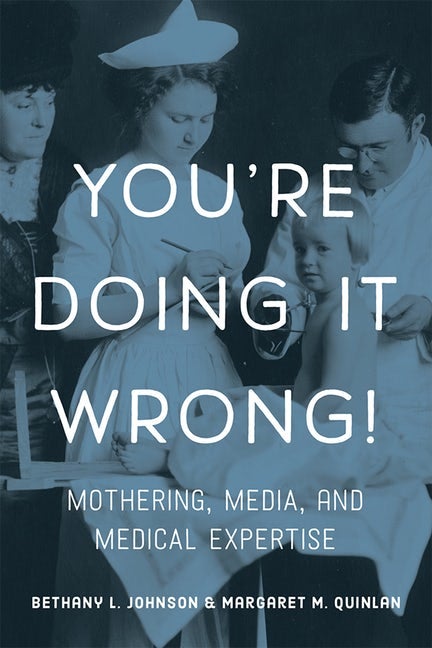

Earlier this year, I spoke with Margaret Quinlan, co-author of the newly released book You’re Doing it Wrong! Mothering Media and medical expertise. Margaret and her co-author Bethany Johnson explore the history of advice that pregnant people and parents receive, all the way up to today and the influence of social media. Margaret and I explored a few specific topics in the book along with her experience writing it while pregnant. Enjoy!

Jocie: I’d love to start by hearing about the overarching message of the book and what motivated you to write it.

Margaret: We were interested in health crises that birthing people face – mostly female-identifying bodies – from preconception through early toddlerhood, the “early cycle of motherhood”. We had several peer-reviewed research articles already regarding infertility, and were also interested in pregnancy behavior, childbirth, the postpartum stage, and the early toddler stage. What did these crises look like in terms of medical expertise from the early 1900s—sometimes a little earlier – and all the way to the present? I’m in Communications Studies, so we wanted to explore some of the messages women received throughout history. Bethany Johnson, my research partner, is a medical and gender historian. And we also wanted to see what is happening today with social media, because we spent so much time looking at expertise discourse in newspapers, magazines, doctors’ papers, letters, casebooks, and so on. On social media platforms, we become interested in why people were asking certain questions, what and when they posted, and we tried to figure out where some of the messages we see today started and how they have shifted or not shifted throughout time. For example, why do people hear about what to eat (or not to) and how to exercise (or not to) when they are pregnant? A lot of the messages people still hear today are actually from the late 1800s and early 1900s. It takes longer for messages to shift than we might expect, especially when people talk about how quickly advice changes. It does and it doesn’t.

Jocie: Fantastic. And when I was looking at the book, one thing that struck me as quite similar to some of our work at Expecting More is the focus on history and the importance of history in examining where we are today. I’d love to know your perspective on why it’s important to examine our past.

Margaret: It’s important because we tend to perpetuate a lot of myths over time. For instance, we still tell women who are going through infertility “just to relax”. That is something that is seen throughout history, and “just relaxing” has most likely not gotten anyone pregnant. We found versions of the message beginning in the 1850s, and we found an article written by a female doctor in 2008. It was fascinating (and sometimes slightly horrifying) for us to look at some of those messages but also to examine why we still see them. One thing that stood out to me when writing it was that we still see a lot of these messages today because it’s so much easier to blame the woman than it is to change systems or institutions—you know, structural change, right? It’s easier to tell a woman who’s pregnant that she shouldn’t be putting herself at risk with toxins than it is to change the culture and the systems that have led to the way we produce foods and who puts toxins in our environment. Sure, it’s individuals, but the scale of industrial output of toxins is orders higher—and as an individual I can’t control that, but socially I’m somehow still to blame for it. It’s easier to make the pregnant person responsible. That message became really clear as we were researching the different health crises, and we were writing about where the blame was placed.

Jocie: That’s interesting. And I was particularly interested in the Twilight Sleep chapter. One thing I was drawn to within that was the role of the lay people in popularizing Twilight Sleep. That was something I didn’t know about before. The role that the non-expert has in shifting care seemed to be a thread in the book – I’d love to know more.

Margaret: That was fascinating because it was the first time women and doctors were having conversations (past each other, in some cases, but there was still a dialogue) in newspapers such as The New York Times and The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and in magazines such as McClure’s – which was a powerhouse then in terms of expose and muckraking journalism – and Ladies Home Journal. And it was fascinating because suffragists and really empowered feminists at the time were the ones who thought that having a Twilight Sleep birth was the epitome of empowerment. They didn’t want to be awake during their birth because most people believed at the time it was too taxing on the mental and emotional energy of “civilized” (white) women. (This was the same energy people believed women would waste by getting an education and not “relaxing” into a female role and thus end up infertile.) Initially, the doctors in the United States were pretty against it and kept saying that they didn’t think it was safe, so some women even went over to Germany – on the eve of World War I! – to experience the procedure. They came back and tried to teach their doctors. And they had these conversations where the women knew a lot about the method and did that advocacy work. As Dr. John Polak of Long Island Hospital in New York noted at the time, the patients were demanding it and they were just attempting to keep pace with demand.

For me, one thing I thought about when going through the Twilight Sleep Association documents and the communication the doctors and women were having is that in ways, they pushed birth into the hospitals. At the time, hospitals were very dangerous places for babies and women because of hygiene issues, and we didn’t know much about how things spread. So, I found that part intriguing. It was these feminist women who were responsible in many ways for us giving birth in hospitals. So what is interesting is that again, in the 1960s and 1970s it would be feminist women taking birth back OUT of the hospitals, and into homes and homesteads a la Ina May Gaskin, whose theories are the bedrock of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiatives we see today. What we wanted to make clear is that what is perceived as best changes drastically over time, even among folks with the same label, such as “feminist.”

It’s important that when looking at the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, we think about the role of lay individuals in where we are today. You can see on social media; some women are posting “I don’t want to breastfeed my child. I’m giving birth in a Baby Friendly Hospital; how can I get around that?” And women will post within seconds saying “bring your own formula, put a sign on your door, bring your pacifiers” – do all these different resistance tactics. They’re really creating their own advocacy for what they see as empowerment in the healthcare system. It’s also interesting because doctors and nurses will be chiming in on social media giving advice saying “I’m a nurse at this hospital and this is what I would do.” It’s captivating because some of them are putting their own expertise out there and potentially putting their own careers at risk. It’s riveting to see how these conversations unfold.

Jocie: Yeah, that’s interesting. The Twilight Sleep instance is a fascinating example because I think the role of the layman is so important, and I think the way to achieve structural change is for people to demand it and organize and advocate. And with Twilight Sleep, my interpretation of it is that a lot of instances it was these really wealthy women advocating for something that was so specialized and can only be given in the way that they want it to women with resources. And it scaled in a way that was assembly-line birth for women who didn’t have those resources and got worse care because of it. And I think that’s an important lesson for people who are advocating for any cause. It’s perhaps quite obvious these days, but just the need to include the most marginalized in that advocacy and to understand how it will scale to people who might not have the same resources as those advocating for change or might not have the opportunity for their voices to be heard.

Margaret: Yeah, and it was interesting too because there were so many myths about women of color and about how they didn’t experience pain the same way. A lot of those stereotypes that we’ve moved past in a lot of ways but are still a part of our healthcare system. So, paying attention to who doesn’t have access to certain treatments and how they’re being promoted by celebrities is something that really interests me.

Jocie: Yeah. So what content from the book felt the most relevant for today?

Margaret: My passion is really for the infertility chapter because that’s where work work began. I didn’t experience infertility per se. I knew I was going to have children later and it could potentially be part of my story – I just didn’t know what my path to parenthood was going to be. I was working with Bethany, who was going through infertility as we were doing the work. She got a terrible voicemail left on her phone while we were in New York City, collecting Twilight Sleep data. The phone call came in at 7 in the morning while she was in the shower. The voicemail said that her fertility treatment wasn’t going well and she needed to call the office back. It was 7 in the morning and the office didn’t open until 9, so she couldn’t get ahold of the embryologist. So it was that whole conversation – even the way the voicemail was left with “have a great day!”. Now that I’ve been studying it, I’ve noticed all of the things that I’ve said to people thinking I was being supportive but realizing that I was giving advice for something they had probably tried. So that chapter is close to my heart, and it just made sense that once Bethany was able to conceive that we went through the stages of the “lifecycle of motherhood” together. We were both having our children at the same time, so we were already going to be spending this time on social media and having our own crises, so that chapter was really where my passion started in this area.

Jocie: That must have been so fascinating going through the process of research while pregnant and experiencing it personally.

Margaret: Part of me thought I might as well be productive and “collect data” while I’m going through this. And at times it was a very unhealthy project to be doing. Our baby loss chapter – we had to figure out when to write that one, because it wasn’t the right time in our lives to be writing about that difficult topic. The whole process of writing and researching medical crises was therapeutic in a lot of ways. I’m glad we did it, but I don’t know if at another time in my life it would have felt as relevant or passionate about the issues we discuss.

Jocie: Thank you. Is there anything else that you think would be relevant to our readers or anything else from your experience of writing the book that is really salient and you’d like to share?

Margaret: One message I take away from it is that I used to be the first person to jump in on those social media posts and give advice, and now I’m more interested in why that person is posting at 3 in the morning about their child’s rash or a pregnancy symptom. I know there are other ways we can support people in those moments that doesn’t involve giving a tip or suggesting something. One thing my co-author, Bethany, started doing was saying “I see you’re scared. Can I Venmo you $5 for a coffee in the morning. I know it’s going to be a long day.” So, there are other more creative ways that we can support people who may feel pretty alone and are navigating some complicated circumstances during this period.

Jocie: It seems like a lot of times it’s just validation that other people have been there before. People aren’t necessarily asking for advice but just “I’m going through this and I feel alone.”

Margaret: Yeah and people don’t know. I think everyone is so afraid that everything they do will be judged or will make a mistake that will affect a child’s IQ or do something that will negatively impact them, but if you look at when dads ask questions on social media, they get dad jokes back. So why is it that everyone is saying wild things to moms – watching those conversations unfold can be painful but there’s definitely more happening in our culture that’s leading to why we’re doing it. And I’ve done it too. I’ve posted at 3 in the morning and connected with some people who gave me great advice when my son was falling off the growth curve and those kinds of situations. I’ve donated breastmilk, and I think there are a lot of great moments that happen on social media, and I want to see those continue, but I also have reservations.

Jocie: Social media is such a double-edged sword. On one hand, it can help people connect and share but then it can put decisions out there for everyone to pick apart.

Margaret: Totally. We’re all doing our best!

Jocie: It’s quite an era we live in. Thank you so much for talking to me!

Margaret M. Quinlan is an associate professor in the department of communication studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She explores how communication creates, resists and transforms knowledges about bodies. She critiques power structures in order to empower individuals who are marginalized inside and outside of healthcare systems. She authored approximately 40 journal articles, 17 book chapters and co-produced documentaries in a regional Emmy award-winning series. She co-authored You’re Doing It Wrong! Mothering, Media, and Medical Expertise (Rutgers) with Bethany Johnson.

Bethany L. Johnson (MPhil, M.A.) is a doctoral student in the history of science, technology and the environment at the University of South Carolina and an associate member to the graduate faculty and research affiliate faculty in the department of communication studies at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She studies how science, medical technology, and public health discourses are framed and reproduced by institutions and individuals with structural privilege from the 19th century to the present. She has published in interdisciplinary journals such as Health Communication, Women & Language, Departures in Critical Qualitative Research, Journal of Holistic Nursing, and Women’s Reproductive Health. Her book, co-authored with Dr. Margaret M. Quinlan, You’re Doing it Wrong! Mothering, Media and Medical Expertise is available now through Rutgers University Press.