By Michele Kulhanek

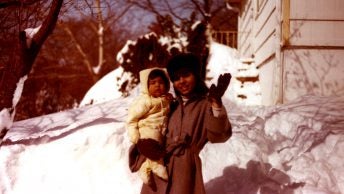

I was 18 about to give birth to my firstborn and scared to death. No one took the time to explain what was happening to me that day. There must have been twenty people in and out of the room, mostly residents who were there to learn how to be doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and so on. I felt stigmatized, vulnerable, and powerless, like I didn’t have a choice in anything: who was allowed in my room to observe or who was performing my cervical exams. Unknowing at the time, these experiences would be a fundamental part of my decision to become a labor and delivery nurse.

Historically, the relationship women have had with the healthcare system has been disempowering to say the least. A lot has changed in health care since I delivered my daughter 31 years ago, at just 30 weeks gestation, from the approval of surfactant use in preterm babies to help them breathe (1990) to shared decision-making and prioritization of the patient experience. We’ve come a long way, but we must still reckon with our history.

Over time, we’ve continued to move the needle in perinatal care, but as COVID-19 sweeps the nation, I’m worried about the potential to backslide. With limited data on the effects of the virus on pregnant people and newborns, health care providers, birthing people, and families are frightened. It’s natural for the unknown to cause alarm for everyone, especially for providers who are used to working in a system where they’ve been all-knowing, but even when situations are dire enough to warrant panic, panic is never productive.

I worry that many healthcare providers are acting out of fear – fear of the unknown, fear of litigation, fear of placing themselves and their families at risk, because they don’t have the appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and evidence-based knowledge to keep themselves safe. But we cannot afford to go back. We must continue to partner with our patients. We can find ways to protect our health care workers AND provide the best care possible. We don’t have to make a choice to do one over the other. We can do both.

In many ways, the reaction to COVID-19 has negated what we know to be best practices, such as limiting support persons and doulas and separating newborns from suspected or COVID-19 positive moms. I think we would be remiss if we did not pause and consider the long term effects of our actions; These most restrictive approaches may cause more harm than good – trauma, postpartum depression, decrease in bonding and breastfeeding. Even without COVID-19, birth is an especially vulnerable time and we must minimize collateral damage – no one will come out of this unscathed.

Take Kaity for example, a well-educated woman who recently gave birth in the D.C. area. Kaity was intending to give birth at a birth center, but on the day she went into labor, she informed her midwife that her husband had a slight cough, and she was told she needed to go to the hospital to deliver. Because of this, Kaity was considered a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19 and was told her husband could not be at the hospital with her. Leaving her husband at the door of the hospital was horrible, she said. Even though she had given birth four times before, she relied heavily on her husband’s support to get her through contractions. This time she felt out of control. She understood the precautions and policies – she was tested for COVID-19 at the hospital, and she wore a surgical mask throughout labor to protect the healthcare providers from possible exposure. For Kaity, not having the option of choosing another support person felt wrong. She was alone. Luckily, Kaity’s mom is an obstetric nurse living in the Pacific Northwest, and she had told Kaity what she might expect and talked to her about her choices during and after labor. Even though Kaity was clear about wanting to keep her baby with her after delivery, she could hear judgement and shaming in the voices of staff despite the diligent precautions Kaity took with her newborn. Kaity wanted to go home to be with her support and other children as soon as possible, and she recalled the pediatrician informing her that if she went home early, that the doctor would not sign off on her discharge and her insurance would not cover her hospital stay. She felt coerced.

Not all women are as privileged as Kaity. Imagine a Black woman, who is aware of the alarming differences in maternal mortality in the U.S., trying to make her wishes known. Anecdotally, we know that when Black women challenge the system they are seen as being confrontational or hostile – having their voices heard was a struggle long before COVID-19 . We were just beginning to bring this to light before the pandemic – hearing the harsh realities that Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women and knowing that many of those deaths were likely preventable was a call for systematic change. What we have on our hands now is a crisis within a crisis, but backsliding is not an option. We need to reflect these truths in our healthcare decisions and policies in order to ensure equity and aid in the healing of generations. We must be nimble and responsive to the needs of all populations we serve, in getting doulas back at the bedside as an integral part of the birthing team and centering the patient experience.

The recently updated guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) aims to assist hospitals and clinicians in applying broader guidance, “on a case-by-case basis, using shared decision-making between mother and the clinical team”. These guidelines are great in theory, and maybe even as policies on paper, but how do they play out in reality? Do hospitals have what they need to meet the needs of their patients and provide individualized care? Are women really hearing all of their options? And maybe more importantly, are they hearing the options in a way they can understand? We need to provide people the tools to ask the right questions to make the right choice for themselves and their families.

The first step to equitable care is to re-evaluate these recommendations, guidelines, and policies as we learn more and ensure that they work for all people. Even with all of the complexities and nuances of COVID-19, we must still do more to support people of color, people with different birth beliefs, people with diverse cultural beliefs, and people with language barriers. Just because we don’t have solid evidence on the effects of this virus, doesn’t mean we ignore what women know. We need to honor the fact that women have knowledge, experience, and intuition about their own experiences and bodies that we as health care providers don’t have. As we move forward, we must find ways to integrate our educational and experiential knowledge with that of our patients.

Women who are PUI or COVID-19 positive have a right to make a decision that is best for them and their babies in regard to support persons, breastfeeding, and separation or rooming-in with their newborns. They deserve to hear the risks and benefits of both, free of coercion or shame. Too many birthing people do not realize they have a choice and it is our obligation to ensure they do.

As a labor and delivery nurse, Michele has worked as a staff nurse, assistant nurse manger, and perinatal educator in a community hospital, as well as in an academic hospital providing care to high risk antepartum, intrapartum, and postpartum patients.

Michele maintains certification in In-Patient Obstetrics and Electronic Fetal Monitoring, Michele is highly involved in the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) at the state level as Washington AWHONN’s Secretary Treasurer, Electronic Fetal Monitoring Instructor, and at the National level serving on the National Membership Committee.

Michele speaks on perinatal loss, trauma informed care and human trafficking awareness to nurses across the nation. Michele serves on Ceres Chill’s Scientific Advisory Board and is also the Board President for Innovations Human Trafficking Collaborative, an anti-trafficking non-profit.

On a personal note, Michele is married with 3 adult children and 1 grandchild. She lives in Washington State where she works to improve perinatal care through quality improvement strategies. In her free time she can be found in her garden, playing with her grandson, or near the water.